Choosing the right sustainable material for food packaging has become a major priority for brands, manufacturers, and consumers. As more companies compare PLA vs PBAT in their search for eco-friendly solutions, one question continues to stand out: which material performs better for real-world applications in the food industry?

The pressure to select an environmentally responsible material is stronger than ever. New regulations, rising consumer expectations, and global sustainability goals are pushing businesses to explore bioplastics that reduce plastic waste without compromising functionality. Yet the challenge remains clear. Many decision makers are unsure how different bioplastics compare, especially when both materials seem to offer similar benefits on the surface.

PLA and PBAT are two of the most widely used biodegradable materials in sustainable food packaging. PLA is produced from renewable plant sources and is known for its rigid structure and clean appearance. PBAT is a flexible and fully biodegradable polymer valued for its durability and versatility. Because both materials support eco-friendly packaging goals, understanding the differences in PLA vs PBAT has become essential for companies trying to make informed choices.

This article will guide you through the key differences between the two materials, including their properties, biodegradability, performance, and best use scenarios. By the end, you will have a clear understanding of which option aligns better with your packaging needs and sustainability objectives.

PLA vs PBAT Overview

PLA (poly‑lactic acid or polylactide) is a biodegradable polyester made from renewable resources (e.g., corn starch, sugarcane) that has gained traction for packaging.

PBAT (poly(butylene adipate‑co‑terephthalate)) is a biodegradable copolyester usually derived from fossil feedstocks, with high flexibility and compostability under appropriate conditions.

Raw Material Composition Comparison

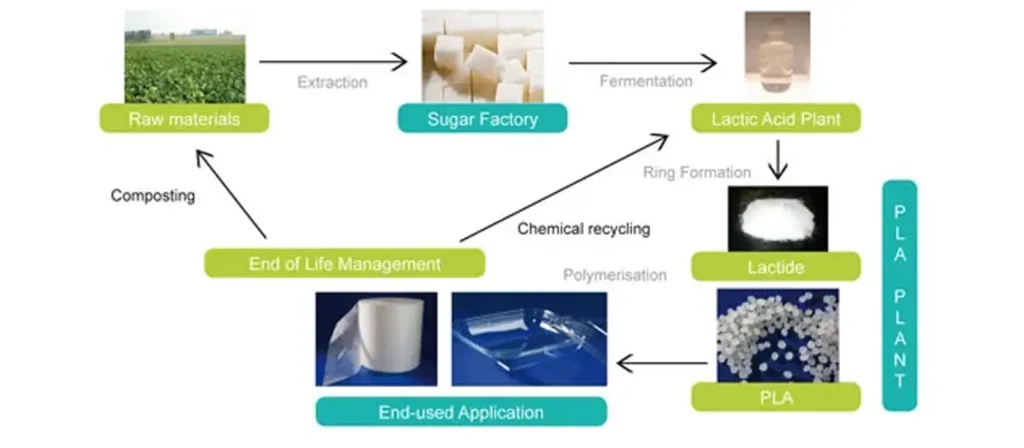

PLA is derived primarily from renewable agricultural feedstocks. Specifically, lactic acid or lactide (a cyclic form) is produced via fermentation of sugars from corn starch, sugarcane, cassava or other biomass. Because the monomer is bio‑based, that gives PLA an immediate marketing advantage in “bio‑based” packaging solutions and aligns with many sustainability narratives focusing on renewable resources.

By contrast, PBAT is a random copolyester composed of butanediol, adipic acid and terephthalic acid (or equivalents). Although some developments aim to increase the renewable portion of PBAT, the predominant commercial form remains fossil‑based or partially so. According to one summary, PLA originates from renewable plant resources, while PBAT originates from petroleum resources.

From a sustainability lens: using renewable feedstocks gives PLA an advantage for “bio‑based” credentials. On the other hand, PBAT leverages existing petrochemical infrastructure, which may provide cost and processing scale advantages. Some key distinctions:

- PLA: Bio‑based raw materials, non‑renewable energy used in processing, high reliance on agricultural feedstock.

- PBAT: Fossil‑based feedstocks, but engineered for biodegradation and flexibility.

- Blends: Often PLA is blended with PBAT to balance properties and cost, so pure composition rarely tells the whole story.

Chemical Properties

The molecular architecture and chemical behaviour of PLA and PBAT affect everything from processing to stability and degradation.

PLA: Aliphatic Polyester from Lactic Acid

PLA’s repeating unit is derived from lactic acid (or lactide). It is an aliphatic polyester. It typically has a glass transition temperature (Tg) in the region of 60‑65 °C and a melting temperature around 150‑160 °C (depending on crystallinity and stereochemistry). Because of its ester linkages, PLA is susceptible to hydrolysis under certain conditions (moisture + heat). That characteristic contributes to its compostability under industrial conditions.

PBAT: Semi-aromatic Copolyester

PBAT is a random or block copolymer containing butylene‑adipate and butylene‑terephthalate segments. The inclusion of terephthalate (aromatic) segments gives PBAT enhanced toughness and ductility, while the adipate segments support biodegradation. PBAT’s melting point is typically lower than PLA, in the region of 100‑120 °C as some literature states. Its glass transition can be quite low (even negative in some cases) owing to the flexible adipate segments.

Physical Properties

The physical performance of PLA vs PBAT dictates how they behave in real packaging systems: how they feel, how they respond to stress, and how they perform across the supply chain.

- PLA exhibits relatively high tensile strength and modulus compared to many biopolymers but suffers from brittleness (low elongation at break).

- PBAT exhibits much greater elongation at break, higher impact resistance, and better flexibility than PLA. For example, some PBAT/PLA blends show deformation to hundreds of percent elongation.

- Thermal resistance: PLA’s heat deflection and use‑temperature are higher compared to PBAT, which limits PBAT in high‑temperature applications.

- Barrier and film behaviour: As flexible films, PBAT is well suited to mimic low‑density polyethylene (LDPE) behaviour, whereas PLA is more rigid and may be less suited to thin film stretch applications.

Biodegradability and Compostability

PLA is biodegradable under industrial composting conditions—typically requiring elevated temperatures (~58 °C or higher), sufficient humidity and microbial activity. In less controlled environments (home compost, soil, marine) PLA may degrade much more slowly, sometimes decades. The hydrolysis of ester linkages converts PLA into lactic acid, which is metabolised by microbes.

PBAT also is industrially compostable, and in some tests has shown faster degradation than PLA under the same conditions. Some studies suggest that PBAT’s biodegradation may be somewhat better in certain composting environments. However, as with PLA, in non‑industrial environments (landfill, marine) the degradation may still be highly limited.

Environmental Impact

The environmental impact of packaging materials extends beyond their end-of-life stage, encompassing raw material sources, production energy consumption, emissions, reuse/recycling potential, and degradation byproducts. Several factors warrant consideration when comparing PLA and PBAT.

1. Feedstock and carbon footprint

PLA’s advantage lies in the use of renewable resources (corn, sugarcane) for its monomer production, which reduces dependence on fossil fuels and can lead to lower carbon emissions. PBAT’s reliance on petrochemical feedstocks means it starts from a higher baseline of fossil‑carbon input. However, the total life‑cycle impact will depend on processing, blending, transportation, and end‑of‑life behaviour.

2. End‑of‑life leakage and microplastic risk

Even the “biodegradable” label can mislead. For example, PLA may persist under some environmental conditions (e.g., marine) and behave comparably to conventional plastics from a deterioration timeframe. If packaging fails to degrade as expected, it may contribute to microplastic accumulation. PBAT, while more degradable in composting, still requires appropriate waste stream management; if it enters landfill or environment without proper composting, degradation can be limited.

3. Manufacturing energy and co‑processing

The energy intensity of manufacturing PLA can be high due to starch conversion, lactic acid polymerisation, and finishing. Similarly, PBAT manufacturing is complex (copolymerisation, high‑vacuum polyester synthesis).

Manufacturing Process

Packaging performance and cost are greatly affected by manufacturability: how the material can be processed, what equipment is needed, and what limitations exist. In PLA and PBAT, differences in processing influence which material is appropriate for which packaging form.

PLA Processing

Because PLA has a higher melting point and narrower thermal window (sensitivity to moisture, risk of degradation), it sometimes requires more careful processing. According to De Luca et al. (2023) in the journal “Inventions”, PLA exhibits a narrow processing window and a slow crystallization rate, which impacts its processability during melting. PLA is extremely sensitive to high temperatures, moisture, and shear forces during melt processing. PLA can be processed through conventional thermoplastic methods: injection moulding, extrusion, thermoforming, and film blowing—but it may require drying and controlled thermal conditions to avoid hydrolysis and brittleness. Factors such as crystallisation rate, cooling profile, and annealing processes are often tailored to achieve desired heat resistance and mechanical integrity.

PBAT Processing

PBAT is more flexible, has a lower melting temperature, and is often easier to extrude for film, blow film, cast film, or even injection mould. Pietrosanto et al. (2020), in their study published in Polymers, demonstrated the successful production of blown films using PLA/PBAT blends across various composition ratios. Their results confirmed that these blends could be processed effectively using conventional film extrusion techniques and were suitable for applications such as chilled and frozen food packaging. The researchers noted that incorporating PBAT into PLA significantly enhanced film flexibility and ductility, enabling better mechanical performance in flexible packaging applications.

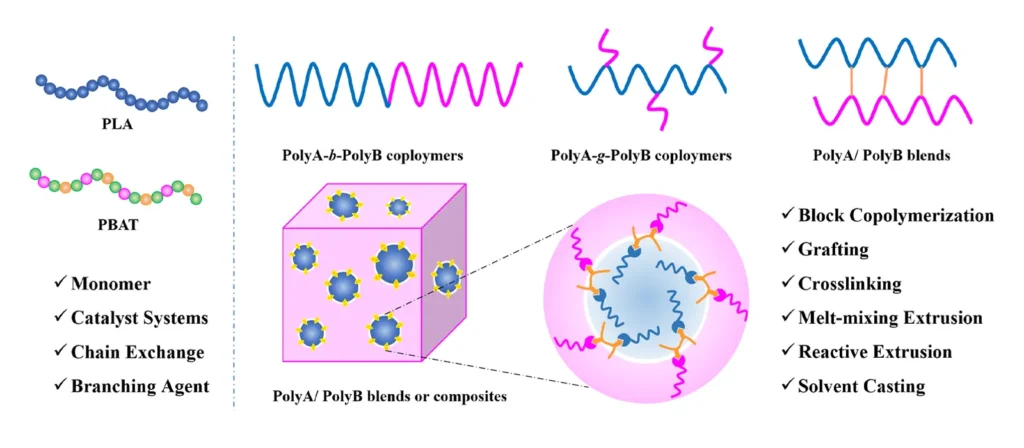

Blends and Compatibility

Due to the complementary nature of PLA and PBAT, many industrial solutions adopt blends of both to combine rigidity + transparency (from PLA) with flexibility + toughness (from PBAT). But this requires compatibilisers because PLA and PBAT are often immiscible; careful control of morphology is needed to avoid phase separation and poor mechanical/bonding performance.

Transparency and Appearance

For food packaging, consumer appeal often hinges on how the package looks. Transparency, finish, gloss, clarity—these matter for shelf presence and for letting consumers see the product. In comparing PLA vs PBAT, differences in appearance are meaningful.

PBAT typically has a more translucent to opaque matte finish, especially when used in film form. The lower crystallinity and more amorphous character give it less inherent clarity compared to PLA. In many flexible packaging contexts transparency may be less critical, so PBAT’s appearance may be acceptable or even preferable for masking contents.

Shelf Life Comparison

Choosing between PLA vs PBAT for food packaging also means ensuring that the material supports the required shelf life for your product.

PLA:

- Offers decent oxygen barrier properties in some applications.

- Works well for many short- to medium-shelf-life products, especially in chilled or ambient conditions.

- Is often used as part of a multilayer structure or combined with coatings to improve barrier for more demanding products.

PBAT:

- Functions more like conventional flexible films in terms of basic barrier.

- Often used for packaging where barrier demands are moderate, or where product is already protected by inner layers.

Application Areas

Rather than asking in the abstract which is “better,” it is more accurate to ask: In which applications does PLA vs PBAT make the most sense?

PLA: Typical Food Packaging Applications

- Rigid containers, cups, lids: Because of PLA’s clarity and stiffness, it is well suited for display packaging for cold foods, salads, ready meals, beverage cups, transparent clamshells.

- Compostable foodservice ware: PLA is widely used in plant‑based disposable cutlery, plates, bowls, trays in foodservice, especially when accompanied by industrial composting collection.

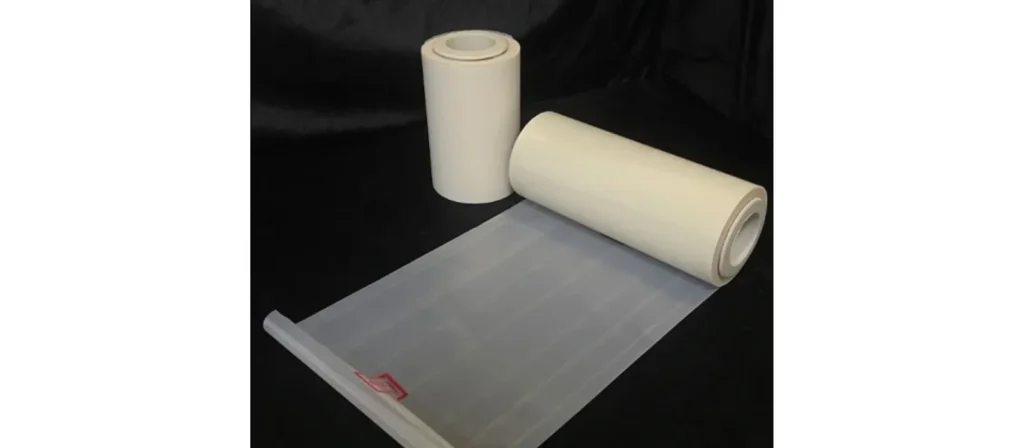

- Films and wrappers: PLA films are used for snack wrappers, consumer bags, but often require coating or blending to improve flexibility or barrier.

- Branding advantage: For brands emphasising “plant‑based packaging” or “renewable materials”, PLA supports the message.

PBAT: Typical Food Packaging Applications

- Flexible films, bags, overwraps and produce bags: PBAT’s flexibility and toughness make it ideal for compostable bags, stretch films for fresh produce, grocery bags, and thin‑walled packaging.

- Laminate structures: PBAT is frequently used in multi‑layer compostable film structures to achieve required mechanical and barrier performance.

- Compostable packaging where handling durability matters: For example, packaging for fresh produce that is handled, stretched, or subject to tear risks may benefit from PBAT‑rich formulations.

- Coatings or barrier layers in packaging that is compostable: PBAT may act as flexible inner layer, with PLA or other polymers as structural or barrier layer.

Challenges of PLA and PBAT Applications in Food Packaging

While both materials offer sustainable advantages, challenges must be addressed when selecting either material for food packaging applications. These challenges are primarily related to material performance, cost, and disposal infrastructure.

Material Properties

PLA is inherently brittle and rigid, which limits its use in applications requiring flexibility. It cannot stretch or bend without cracking unless plasticizers or blending agents are added. It also has a relatively low thermal resistance, typically deforming at temperatures above 60°C, making it unsuitable for hot food packaging unless modified.

PBAT, while more ductile, has lower tensile strength and barrier properties. On its own, it may not be suitable for long-term food preservation due to higher oxygen and water vapor transmission rates. This limits its standalone application for products that need extended shelf life.

Cost Factors

From a manufacturing perspective, both PLA and PBAT are still more expensive than their conventional counterparts, although costs have decreased in recent years due to economies of scale and innovation in production techniques.

- PLA Cost Drivers: High demand for renewable feedstock, energy-intensive polymerization, and limited processing speed in some cases.

- PBAT Cost Drivers: Dependency on petroleum derivatives, synthetic complexity, and blending costs when used in composite materials.

Composting Infrastructure

oth PLA and PBAT require industrial composting conditions—high temperature, high humidity, and sufficient microbial activity—to degrade effectively within a reasonable timeframe. However, such facilities are not widespread, especially in developing countries or urban areas lacking sophisticated composting systems.

Furthermore, many consumers mistakenly discard PLA or PBAT into ordinary recycling bins or household compost bins.

Why Combine PLA and PBAT?

PLA and PBAT are often combined to balance performance and compostability. PLA offers strength and is bio-based but tends to be brittle, while PBAT is flexible and durable but fossil-based. Blending the two improves flexibility, impact resistance, and processability, making the material more suitable for diverse food packaging applications while maintaining industrial compostability.

PLA vs. PBAT Market Trends

The market for biodegradable and compostable packaging materials is evolving rapidly, and both PLA and PBAT are central to that transformation. Understanding current trends helps contextualise how brands and packaging suppliers are using these materials, where growth is happening, and what the future may hold.

- Regulatory pressure: Many jurisdictions are banning or restricting single‑use plastics derived from fossil feedstocks, incentivising compostable or bio‑based alternatives.

- Consumer demand: A rising segment of consumers actively seeks packaging labelled “compostable”, “bio‑based”, “eco‑friendly” and will pay a premium for products aligning with sustainability.

- Corporate commitments: Brands across food and beverage sectors are announcing net‑zero or zero‑waste packaging targets, prompting investment in materials like PLA and PBAT.

- Technological improvements: Advances in polymer chemistry, processing and end‑of‑life systems are driving broader availability and improved performance of bioplastics.

- Film‑format expansion: Flexible packaging, films and pouches are among the fastest growth segments for compostable polymers—areas where PBAT (and PLA/PBAT blends) are gaining share.

FAQs

- Can PLA or PBAT be recycled like conventional plastics?

Both face recycling limitations. PLA has some chemical/mechanical recycling in pilot phases, but infrastructure is limited. PBAT is generally intended for compostable streams rather than traditional recycling. - Is the compostability of PLA vs PBAT equivalent in all settings?

No. PLA often needs industrial composting (e.g., ~60 °C), while PBAT may degrade more easily in soils or broader conditions. Thus actual end‑of‑life environment matters. - Which material is better for a clear rigid food tray?

PLA would typically be the better choice for clear, rigid trays due to its transparency and stiffness. PBAT is less clear and more suitable for flexible film. - Which material is better for flexible pouches or film packaging?

PBAT or a PLA/PBAT blend tends to be better for flexible pouches or films because of its flexibility, elongation and film‑processing performance. - Is blending PLA with PBAT common?

Yes. It combines PLA’s rigidity with PBAT’s flexibility for better performance.

Conclusion

Choosing between PLA and PBAT for food packaging is not a binary decision—it is a strategic one. Each material brings unique benefits to the table: PLA with its bio-based origin and rigidity, and PBAT with its flexibility and processing ease. However, both face limitations in biodegradation infrastructure, mechanical performance, and cost-effectiveness when used alone.

For brands seeking to meet sustainability goals while maintaining packaging functionality, combining PLA and PBAT is often the most viable path forward. With increasing regulation, growing consumer awareness, and expanding composting networks, these bioplastics are poised to play a vital role in the future of eco-friendly food packaging.